The Sacred Harp is the best-known shape-note

song book used in Georgia.

|

| A

Sacred Harp singing | It

was published in 1844 by west Georgians B. F. White of Hamilton (1800-79)

and E. J. King of Talbotton (ca. 1821-44). This tune book—both the

original version and its revisions—has helped promote the style of

unaccompanied singing known as "Sacred Harp," "shape-note," or "fasola"

singing.

Development of Shape-Note Singing

The Sacred Harp uses notation developed by the

progressive New England singing masters William Little and William Smith,

who published the Easy Instructor in 1801. Their shape-note system

was designed to teach sight-reading and enable users to sing complex,

sophisticated music.

The practice of singing the scale in syllables—"Do, re, mi,

fa, sol, la, ti"—originated in Europe long before 1800. Sometimes not

seven but four syllables were used: fa, sol, la, and mi.

|

| The shaped tune

"Wondrous Love" | The

major scale is expressed as fa, sol, la, fa, sol, la, mi, fa. Smith and

Little gave each of the four syllables a shape: a triangle (fa), a circle

(sol), a rectangle (la), and a diamond (mi). The musical phrase (right)

from the hymn "Wondrous Love" shows these shapes in use.

Singing masters taught sight-reading by having students

first "sing the shapes." The line above, for example, would be sung as "La

la sol mi sol la sol mi la la sol." This practice survives in Sacred Harp

singing today. Singers first sing the shapes, or syllables for the notes

of their parts, and then the words.

History

Shape-note tune books and the singing masters who produced

them, as well as the social and cultural forces that affected shape-note

singing, have been widely studied. Scholars have written extensively about

The Sacred Harp itself, its editions, and its survival as the most

resilient of the four-shape books. Neither the Civil War nor the

introduction of seven-shape books and round-note denominational hymnals

extinguished singers' enthusiasm for The Sacred Harp. Nor did the

coming of radio and records or such newer styles of sacred music as

gospel.

Singers today are likely to use one of two revisions. The

B. F. White Sacred Harp, known as "the Cooper book," descends from a

1902 revision by W. M. Cooper of Dothan, Alabama.

|

| Singing from the

Sacred Harp | It is

widely used in south Georgia, north Florida, and the Gulf region extending

to Texas. It has a strong following among white singers but is also

favored by African American singers in that area. (The Colored Sacred

Harp, by Judge Jackson of Alabama, a Cooper book singer, was published

in 1934. It contains shape-note songs composed or arranged by Jackson and

other African American singers. This collection has been popularized by

Alabama's Wiregrass Singers.) The other revision, arising from White's

circle of friends, children, and pupils, came to be called "the Denson

book." It began with a 1911 revision chaired by J. S. James of

Douglasville, Georgia. This edition, in turn, was the basis for revisions

by members of the Denson family of Alabama. Thomas J. Denson established

the Sacred Harp Publishing Company, which published The Original Sacred

Harp (Denson Revision) in 1936. The 1991 edition of The Sacred

Harp was produced with an editorial committee headed by Hugh McGraw of

Bremen, Georgia, where the Sacred Harp Publishing Company is now located.

This 1991 book is the choice among singers in northern Georgia and

Alabama; moreover, it is the edition most widely used nationally and

internationally.

Today's popularity of Sacred Harp singing owes much to B. F.

White and the subsequent singers who collected and arranged tunes, taught

singing schools, and wrote about and faithfully supported shape-note

singing. Especially deserving mention is Hugh McGraw, who has worked

tirelessly to promote learning and to reach new singers. McGraw was named

a National Heritage Fellow in 1982 for his efforts on behalf of Sacred

Harp singing. Another singing master is Richard DeLong of Carrollton, who

served with McGraw and others on the 1991 revision committee. Among

Georgia singers who use the Cooper revision, David Lee of Hoboken has

traveled and taught. The efforts of these singers and many others have

spread Sacred Harp singing, and today singers gather in Chicago, Boston,

and Albuquerque, as well as in Tallapoosa, Atlanta, and Birmingham.

A Sacred Harp Singing

Sacred Harp singings follow a characteristic pattern

established by White and maintained by such later singing masters as the

Densons and McGraw.

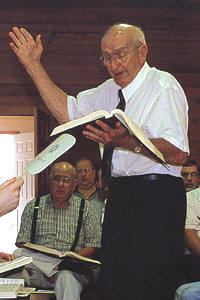

|

| Singing Leader |

The

singers sit in a hollow square with four sections—tenor, bass, treble, and

alto. Tenors face altos, and trebles face basses. In a manner reminiscent

of the singing schools, a leader chooses songs that are called a "lesson"

and the singers are the "class." Leaders take turns standing in the center

of the square, beating time in a traditional method appropriate to the

song's time signature. Singing continues all day, with a noontime break

for dinner on the grounds. These singings require stamina and musical

athleticism, since the group may sing as many as ninety songs in the

course of one day.

The sound of Sacred Harp may vary a bit from region to

region, and white singers have different styles from African American

singers. But regardless of location or voices, Sacred Harp sounds unlike

academic choral singing or gospel singing in which melody dominates and

harmony embellishes and supports it. The tunes of The Sacred Harp

do have a melody part, the tenor, but it coexists with three other parts

in no way merely supportive of a dominant melody. The parts in shape-note

singing are so distinct that traditional tune books like The Sacred

Harp print them on separate staves, displaying what is called

dispersed harmony.

Gapped scales (having less than the usual seven notes) and

unusual harmonies help account for this traditional music's characteristic

sound. Also unique is the doubling of two parts, both men and women

singing tenor and treble. Untrained voices prevail, so the singing sounds

loud and exhilarating. Although singers in different communities may

prefer slower or faster times, leaders set the tempo. One occasionally

hears singers warn each other, "Watch the leader," when the class goes too

slowly or runs over a fermata (pause sign).

Sacred Harp Tunes

In the 1844 Sacred Harp and its various revisions

many writers' works appear, but most of the texts are eighteenth-century

English hymns by such poets as Isaac Watts,

|

| Singing from The Sacred

Harp | Charles Wesley, William Cowper, Samuel

Stennett, and John Newton. Some of these texts, as modified by

nineteenth-century American singers, have acquired choruses in the

camp-meeting spiritual style. In addition to the hymns, the tune book also

includes anthems—passages of prose, usually scripture—and other texts

including odes and "set pieces," words written for a particular tune or

setting.

Some hymn tunes, both English and American, were originally

associated with work songs, sea songs, drinking songs, or similar tunes of

secular folk origin. Some, like the familiar "Old Hundred," came from the

psalm-singing tradition. Others are "fuging tunes," complicated settings

in a style originating in the English Renaissance and based on metrical

psalm-tunes. The fuge, like the fugue of Bach and other

eighteenth-century composers, takes its name from a word that means "to

fly" or "to flee," but a fuging tune is not the same thing as a fugue. A

shape-note fuging tune has one or more sections with staggered entrances;

the various parts begin the fuge in different measures, rest, enter again,

and sing over each other, indeed making the music soar.

Composers of fuging tunes and other settings include New

Englanders William Billings, Timothy Swan, and Daniel Read and a number of

Georgians as well: White and his coeditor, the young E. J. King; John P.

Reese and his brother H. S. Reese, born in Jasper County; and Elder Edmund

Dumas of Forsyth. (Contributors did not always compose the tunes

associated with them. In The Sacred Harp a tune may be ascribed to

a composer, an arranger who learned it from older singers, or merely to an

earlier tune book.) Some tunes, either from their origin or because of

shaping through generations of traditional singers, may properly be called

folk tunes.

Sacred Harp singing preserves traditional ways from earlier

times but is also a living art form in which composers write new songs.

The Sacred Harp, 1991 Edition, for instance, contains notable new

compositions along with texts and tunes from previous centuries.

Since 1844 Sacred Harp singers have defined, nurtured, and

passed along their art and their beliefs. Participants agree on two

points. First, this singing is democratic and independent. Free of

denominational ties, it represents a religious expression outside the

limits of any church's doctrine and discipline. Second, it is for singers,

not listeners. Those who sing enter into a community where sophisticated

musical skills, veneration for singers of previous generations, and

constant immersion in the poetry of the songs make for a powerful

experience.

Suggested Reading

John Beall, Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp

and American Folksong (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997).

The B. F. White Sacred Harp: Revised Cooper

Edition, ed. John Etheridge, et al. (Samson, Ala.: Sacred Harp Book,

1992).

Joe Dan Boyd, Judge Jackson and the Colored Sacred

Harp (Montgomery: Alabama Folklife Society, 2003).

Buell E. Cobb Jr., The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its

Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1978).

Dorothy D. Horn, Sing to Me of Heaven: A Study of Folk

and Early American Materials in Three Old Harp Books (Gainesville:

University Press of Florida, 1970).

George Pullen Jackson, White Spirituals of the Southern

Uplands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933).

The Sacred Harp, 1991 Revision, ed. Hugh McGraw, et

al. (Bremen, Ga.: Sacred Harp Publishing, 1991). |